Today marks ten years since my Dad passed away. I wrote this a year or so ago. It’s not finished, but thought I’d share it anyway, on this day that seems impossible.

STAGES OF FIRE

Sometimes I forget I have the jar. Just yesterday, it surprised me when I opened a drawer I hardly ever open and there it was. It used to hold six ounces of Durkee maraschino cherries, that’s what the yellow label says. The rusty metal lid is stamped 93 cents. The cherries are long gone, probably used in a fruit cake no one really wanted. Now it’s filled with six ounces of Dad’s ashes. Cremated remains. Cremains. I hate the word. It might be the heaviest of word mashups. It’s just not as fun as spork or froyo.

Cremains look about as unfun as you can get. An almost colorless grey, similar to cat litter--the scoopable kind, but a little dustier, with pieces that look like teeny rocks. Rough and sharp cut, like smashed-up gravel on the side of the road. That’s what his look like anyway. I’ve read that no two cremated remains are the same. Their composition is affected by genetics, age, where the person lived, what they ate and drank. I wonder how much of Dad’s ashes are composed of pork chop grease, nicotine, and alcohol.

The woman at the funeral home tried to sell us an urn from the world’s saddest catalog. Pages and pages of receptacles that all looked like something you’d get at the dollar store, but they cost hundreds. Dad would’ve declared it bullshit. We decided to pass. When she told us the box to burn him in would be $400, I could hear him from months earlier. Just throw me over the hill when I’m dead. Who in the hell cares. I won’t care. I’ll be dead. He kind of had a point.

STAGE 1: IGNITION.

Pre-heat. Not affecting anything beyond the immediate vicinity. Characterized by uncertainty.

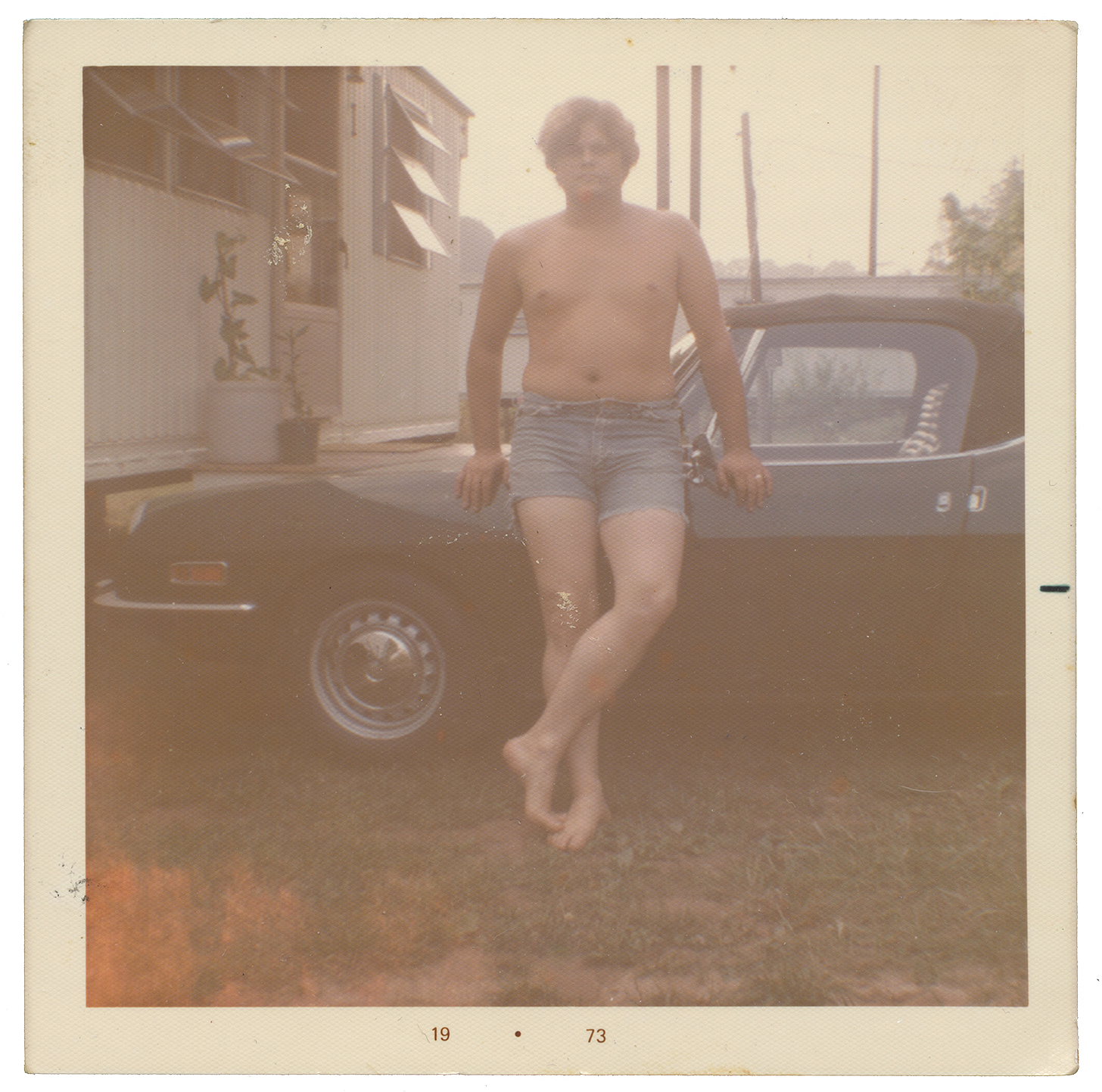

When I was little, I liked to sit on the floor in front of the couch and watch TV with him. The volume was turned up about six times too loud, but his hearing had been blown out from years of racing cars and working beside heavy machinery. He was usually in his outfit of choice--cut off jean shorts, his legs and feet bare beside me. I’d look at the scar on his shin, smooth and purplish pink. I knew them by heart already, but I’d ask him to tell me the stories. He was running through the woods and a stick went plum through his ankle. One time he sliced off the tip of his pointer finger in shop class. The nail grew back but never looked quite right. He’d tell me about his friend who fell in the woods and a stick went right up his butthole. He was ok, but it hurt like hell.

Dad didn’t stop adding to the scars as he got older. New ones joined the collection all the time. There were circles on his forearms from bar bets to see who could leave a lit cigarette laying on their arm the longest. The deep diagonal scar across his nose and smaller ones above his eye, all from going through the windshield of a car and coming out with his eyelids barely hanging on.

Once in a while he’d give me a puff of his cigarette. I wouldn’t inhale, I’d just blow smoke and make him laugh. Mom wouldn’t let him drink at home, so he periodically disappeared to do that, but smoking was full-time. When money was extra tight, instead of buying cigarettes, he’d come home with rolling papers and a tin of tobacco. He’d show me and my brother how to roll them and we’d have a little assembly line going. Sometimes he’d have a bag of filters that looked like tiny marshmallows, and we’d add them to the ends of the cigarettes. I loved the smell of it all, before they were burnt. It smelled like walking in the woods, but sweeter.

STAGE 2: GROWTH.

Harder to control. Fire has established itself. Able to spread and destroy anything in its path.

I was around six when I realized my parents would die one day. I liked to lay on my stomach on the crunchy brown carpet in front of the TV. I had just finished Mask, a movie starring Cher and Eric Stolz, about a boy with craniodiaphseal dysplasia who dies in his sleep. Most people would probably say the movie is about a lot more than that, but that’s the part that stuck with six-year-old me the most.

It had never occurred to me that someone could die in their sleep. How was I supposed to just go to bed when I might not wake up? Mom and Dad tried to tell me I wouldn’t die anytime soon, that I had lots of years ahead of me. Dad tried to comfort me by saying that death is just part of it all, that everyone dies and he and mom would die someday. That had never occurred to me either. I was the opposite of comforted. I wanted to go back to when I didn’t know that they wouldn’t be here forever. That I wouldn’t be here forever.

The next year a kid from school died. His name was Mickey and he was spending the night with his friend who lived right up the road from us. The trailer caught fire while they were asleep. The firemen said that the metal roof was like an umbrella, keeping the heat and flames in and the whole thing just went up before they could stop it. Everyone made it out except Mickey. I felt sick to my stomach when I thought about it. I didn’t know him well. He was older than me, in my brother’s class, but he was someone I’d seen in person, someone I’d rode the school bus with, and now he was just gone. The grownups didn’t save him and all that was left was his little black and white photo in the yearbook.

I’d never actually known a kid who died. I’d heard about my cousin Jackie Dale, but I couldn’t remember him. He was Dad’s brother’s baby, born the same year as me. His mom was drinking and driving, with him in the truck. She wrecked and he went through the windshield and died. Mawmaw had a picture of him in his little casket in her photo album. He was wearing a ball cap, with his tiny hands folded on his chest. It almost looked like he was smiling, like he was just faking it. I would hold my breath when I looked at the picture, worried that somehow the death would get into me.

STAGE 3: DEVELOPED.

Hardest to suppress. A new fuel source can be something as simple as a change in the wind. Most dangerous.

Someone was shaking me and the room was loud. Fire was echoing in my head. Mom’s wild eyes, screaming Hurry! Get up! Someone grabbed my arm and pulled me out of bed. I was out the door and into the night, standing in the driveway in my Garfield nightgown. The gravel was cold and sharp on my feet. Neighbors started coming out of their houses and someone said they called 911. I couldn’t see the flames, but I could smell smoke. Dad grabbed the water hose and ran around to the back of the house. We waited.

The night was glowing yellow. We never got to be outside in the middle of the night, especially not everyone all at once. The moon was like a spotlight shining down, making everyone and everything look like it was on a stage. I decided to do a trick I had, pushing my worries out of the front of my mind and acting how someone cool would act. Like it’s not real life, but I’m on a TV show that people are watching. I’m playing a girl whose house has caught on fire, but I’m just so cool and mature for my age and nothing phases me because I’ve seen it all.

Dad managed to put the fire out before the volunteer firemen got there. He knew the guys who showed up. They said there wasn’t too much damage and it had started from a cigarette smoldering. I didn’t know what smoldering meant, but I knew my sister Heather was in trouble. She’d already been caught with cigarettes once before. Dad had grounded her, but turned out that was just so Mom didn’t get mad at him. He had given her the cigarettes under the condition that if Mom catches you yer on yer own.

Things never seemed to settle back down after that. This is just the short version of a complicated time when nothing felt steady. Everyone fought more and harder. Dad drank more. Heather accidentally caught the house on fire for a second time. I worried more. Eventually Mom and Dad filed for divorce. We weren’t sad about it like the kids in movies are. We didn’t know what took them so long. Mom was awarded custody and the house when the divorce was finalized. Early the next morning, on the day I turned eleven, the house burned all the way down. We weren’t home at the time, but our stuff was in there. Heather was out of town, so it wasn’t her fault this time. The firemen said it was arson, but no one could court-of-law prove who did it. Dad sure wasn’t happy about the divorce, but he never did admit he had anything to do with the fire.

STAGE 4: DECAY

Nothing left to burn. Out of oxygen.

I moved back to West Virginia when I was thirty-four. I’d left after high school and stayed gone until I had this feeling that wouldn’t go away, that I should be there, at least for a little while. Six months after I moved back, Dad was admitted to the hospital. It was the only time I can ever remember him being in a hospital and he was not a fan of being told what to do. There was a designated smoking section outside of the hospital, a little ways from the building, and that was the only place you were supposed to light up. He’d have one of my sisters sneak cigarettes in and would go into the bathroom to smoke. The smoke alarm went off once, but the nurses on duty that day were nice enough to pretend to not to know why. At one point, still loopy from anesthesia, he ripped the IVs out of his arms, demanding to go home while blood sprayed across the room.

In a moment of calm, he sat cross legged in the hospital bed, cleaning dirt from under his fingernails with his pocketknife. He told me every Harrison should carry a knife. He looked so out of place sitting in all that bland sterileness. I hadn’t noticed until then just how skinny he’d gotten. The gown swallowed him up and made him look like some kind of misfit angel who hadn’t gotten his wings yet. He asked me why haven’t you given up on me? Everyone else has. I didn’t know how sick he was. He didn’t know. I thought the drinking was just making his liver angry. It turned out that was true, but also cancer had started in his lungs and already spread through his body. He would be gone in less than two weeks later.

I was left in charge of his will. Executrix. Another word that got on my nerves and wasn’t anything I ever wanted to be. I wasn’t sure why he asked me out of the five of us, but I said yes, not knowing the will would need executrix-ing in a matter of months. But, that part of what he left behind was pretty simple. There wasn’t a lot of stuff to be dispersed among us, no money to get everyone riled up. I thought about how much rich kid fighting there must be when one of their parents dies. I think I prefer our family feuds over mostly intangible things.

He’d written out who got the trailer he lived in, the one he inherited when Mawmaw died. He said who he wanted to get the antique train set his dad gave him when he was a kid, and who should take his dog Lily. She was what he was most worried about. He’d found her a few years before, in the shell of a burnt-out house beside the garage where he and his buddies sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. When I would visit him, Lily would sit at his feet while he scratched her back with one of those wood back scratchers that looks like it has a little hand on the end. A full ashtray was almost always sitting on the couch cushion beside him, with a lit cigarette resting in the little dip in the side. The sun creeped in through the slits in the mini blinds, turning the smoke and dust into sparkly, cloudy paths across the room. The smell would stay on me long after I left, until I showered and washed my clothes.

One of the last times Dad was in my car I kept asking him not to smoke in there. He’d put the cigarette out and then five minutes later light another one. Dad! He smashed the cigarette into the ashtray that only he used. Shit, I forgot. I’d finally give up and tell him at least roll your window down if you’re going to smoke in here. We drove to an antique car show, looking for one of the hot rods he’d built for his friend Coon. It’d been sold long ago, but sometimes he’d see it around. We didn’t find it that day. He got tired after we walked down two rows of cars and wanted to leave. Sometimes on our drives he’d ask to get behind the wheel. He’d find a straight stretch and floor it, to see what the car could really do. He didn’t feel like driving today. When I hit even the smallest bump in the road he winced in pain. After I dropped him off at his trailer, I saw that he had spilled beer on the floorboard and burnt a hole in the carpet on the passenger side. I was annoyed, but not surprised. Now, I look at the burn mark and I’m glad it’s there. An annoyance transformed into a keepsake. A scar left behind.

.

Beautiful and tender. I loved this, and the photo at the end is extraordinary.

Thank you. Real living…thank you.